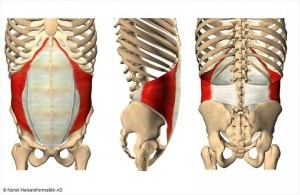

The core is often misunderstood as just the abdominal musculature and perhaps the lower back, but it is actually made up of an ‘inner’ and an ‘outer’ unit. The muscles of the inner unit of the core are the multifidus, pelvic floor, transversus abdominus and diaphragm. These muscles create a cylinder-like, or corset-like, structure around the lumbar spine from the base of the ribs down to the pelvis. These muscles all work together to help stabilize the lumbar spine, the pelvis and the rib cage. They do this through three known mechanisms: increasing intra-abdominal pressure, thoraco-lumbar fascia gain and the hydraulic amplifier mechanism 1.

Stability of the spine, pelvis and rib cage are crucial to prevent injury and to provide a foundation for the limbs to create movement efficiently, powerfully and safely. The more stability created by the inner unit, the more power can be produced through the limbs, and the likelihood of injury is reduced. All movement emanates from the core outwards. This means that the inner unit muscles of the core contract prior to the more superficial phasic muscles. Or to put it another way, the inner unit muscles contract to stabilize the lumbar spine, pelvis and rib cage prior to muscles of the outer unit. For instance, the transversus abdominus, pelvic floor and diaphragm have been shown to contract on average 30 milliseconds prior to an arm movement and 110 milliseconds prior to a leg movement in all directions of limb movement. The outer unit muscles of the trunk contract later than the inner unit muscles and often contract later than the movement of the limb itself. The timing of contraction of outer unit trunk muscles is dependent on the direction of movement of the limb. The difference between the inner unit muscles of the core is that they are controlled by the central nervous system independently of the outer unit trunk muscles. It has also been shown that when one muscle of the inner unit contracts, the other muscles of the inner unit also contract. This suggests that these muscles are on the same neurological reflexive loop.

Abdominal Bracing

In simple terms, pain in the abdominal region or lumbar spine, a lack of physical activity or inflammation of an internal organ can cause these inner unit muscles to be inhibited and unable to contract normally. This leaves the spine exposed, increases the likelihood of injury and reduces the amount of power available. This concept is important to understand when training in the gym. There are many different views amongst experts with regards to training the inner unit. Some suggest not consciously focusing on it at all and instead just stiffening all the abdominal muscles, known as ‘bracing’, to stabilize the spine. Activation of all three layers of the abdominal wall, called “abdominal bracing”, also causes the lumbar extensors to activate, which buttresses those with painful shear instability. Bracing of the abdominal wall activates the back muscles forming a stiffening girdle. In terms of stability there are no agonists or antagonists as all muscles contribute. Bracing appears to be a highly efficient strategy to enhance stability. Proper breathing and bracing of your core muscles when lifting activates your body’s “natural weightlifting belt” .

To practice abdominal bracing:

- Stand or assume a stable position.

- Take a deep breath, engaging your core muscles without excessive tension.

- Maintain this braced position while exercising, remembering to breathe normally.

Benefits of abdominal bracing include improved spinal stability, reduced risk of lower back injuries, and increased power during strength exercises. This concept is vital for weightlifting, functional fitness, or activities requiring core stability. Consider tailoring the training program based on individual assessments, incorporating conscious activation exercises, and progressing towards coordinated movements to effectively address inner unit dysfunction and enhance core stability.

Conscious Activation and Progression:

It’s observed that a significant percentage of individuals may have a dysfunctional inner unit initially. To address this, consider incorporating exercises that focus on conscious activation of the inner unit muscles. The four-point tummy vacuum is an effective starting point. This exercise allows individuals to consciously contract these muscles without having to think about other muscle movements. As confidence in muscular contraction grows, exercises can be progressed to include coordination with outer unit muscles.

The horse stance position is particularly effective in this progression. As the individual becomes confident with the muscular contraction, exercises can advance to include coordination with outer unit muscles . The horse stance position is particularly effective, as the viscera creates a stretch and excites the muscle spindles of the transversus abdominis muscle, enhancing its ability to contract.

To perform the four-point tummy vacuum, follow these steps:

- Begin on your hands and knees, with your hands directly under your shoulders and your knees directly under your hips.

- Take a deep breath in, and exhale, After exhaling, pull your belly button toward your spine as much as possible. Imagine trying to touch your navel to your spine.

- Hold the contraction for 15-30 seconds, or as long as you can maintain good form.

- Repeat this exercise for 10 repetitions, working up to 3 sets of 10 repetitions.

Remember, the key is to focus on the contraction of the transverse abdominis muscle. This exercise helps strengthen your core and improve abdominal control

Recent Comments